A pickup in business and investor confidence, and a hope that inflation and global economic activity might be recovering, drove pleasing performance from investment markets recently in many parts of the world, most particularly in real estate and shares.

However, I find it perplexing that at-risk asset prices such as real estate and shares have maintained these elevated prices whilst underlying economic signals, which normally drive such valuations, are to some extent negative. It seems that the normal relationship sequence between asset prices, interest rates and economic activity is askew. We should by now be enjoying the next strong economic cycle, it being 10 years on from the previous 4%+ peak GDP of 2006/7, but GDP is struggling to stay above 2%. Wage growth, inflation and interest rates should all have risen, but each has fallen. Consequently, government financing is awfully weak, and the ability, or not, for consumers to get on top of mountains of debt is emerging as one of the most important socio-economic issues of our time.

Perversely, it is this fragile economic situation that is supporting share prices, because of the very low interest rates, and corporations’ success in maintaining profit growth via productivity improvements, including the benefits of automation and globalisation (tax and labour), and constrained wages. This concept is broadly known as neoliberalism, a word I expect to hear a lot more frequently in coming years. Essentially, neoliberalism is laissez-faire economics, promoting free trade, deregulation, privatisation of public assets and services, globalisation, lower government spending and fiscal austerity. For a generation now, global policy settings have tended to follow these philosophies.

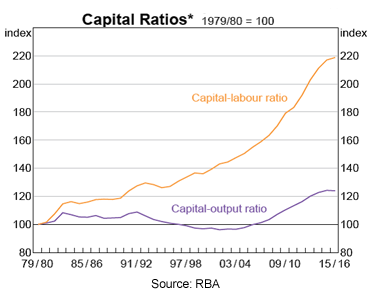

Even the most ardent neoliberal should accept that the consequences and outcomes of such policies are not all positive. Take the global financial crisis for example, to which some of the root cause can be attributed to poorly regulated financial markets. Look also at some of Australia’s economic statistics. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reports each month an ever-increasing capital to labour ratio, which reflects the extent to which automation is displacing human labour. Productivity benefits have been enormous, so company profits and their respective share prices have surged. Yet job growth is stagnant, and under-employment is at an all-time high.

There must come a time, sooner or later (perhaps sooner now, rather than later) that weaker relative disposable income growth of individuals affects consumption spending, and hence leads to an economic slowdown, and lower share prices. There is no clearer example of this at work than the United States, where widespread disaffection caused a political upheaval in the form of Donald Trump, whose constituent voters are expecting him to adopt policies that are distinctly antiestablishment and, in some cases, anti-Republican. Similar populist trends are evident in Europe, perhaps manifest shortly in the French presidential election, and in Italy next year.

The Australian capital to labour ratio has risen dramatically, reflecting a trend towards process and job automation.

The Australian capital to labour ratio has risen dramatically, reflecting a trend towards process and job automation.

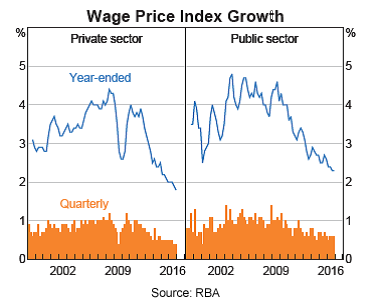

And this has contributed to a sharp decline in wage growth

And this has contributed to a sharp decline in wage growth

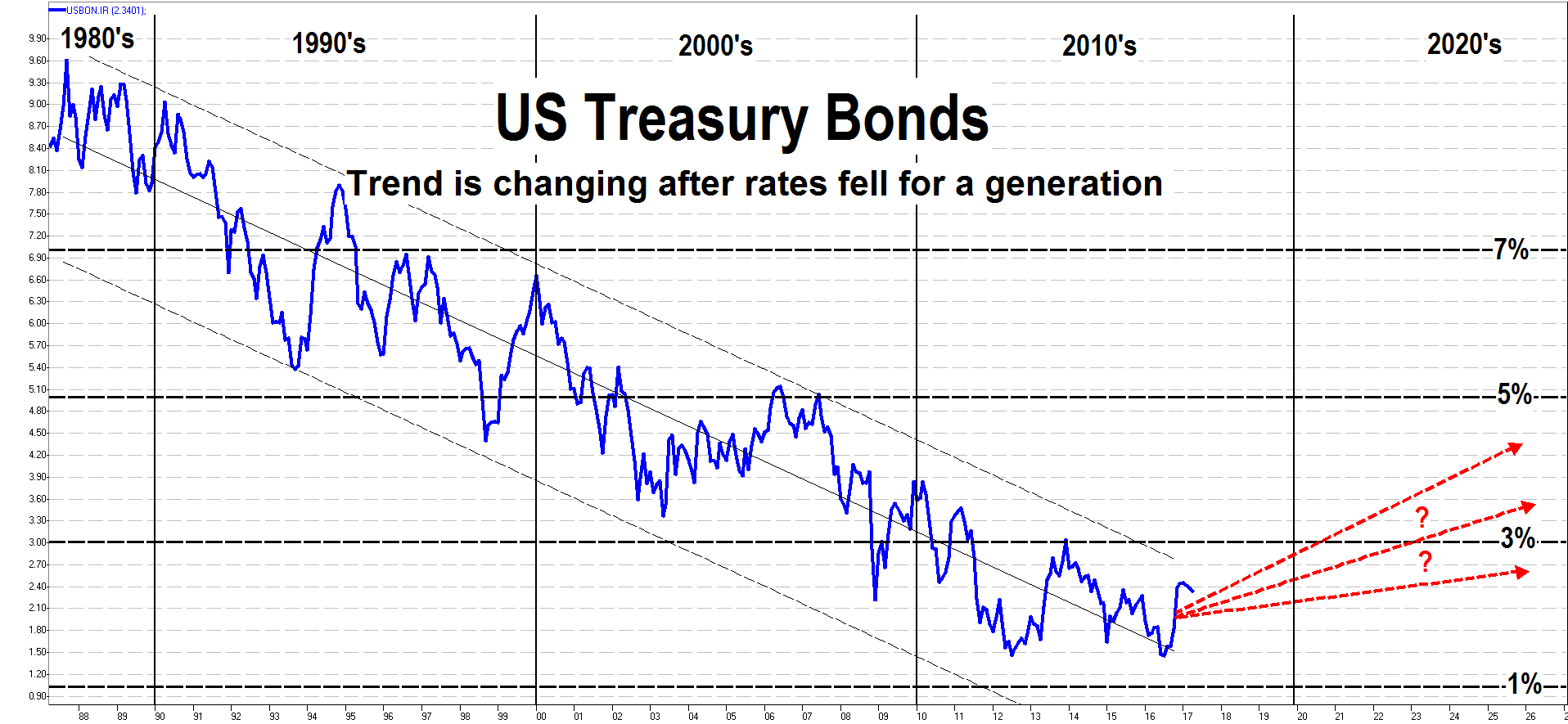

Thirty years ago, towards the end of the 1980’s strong economic cycle, the world’s primary interest rate benchmark, the long-term US Treasury Bond, was yielding 9%. Australia’s long-term bond rate at that time was a staggering 14%. Since then, interest rates have fallen, not for a year or two, or even a business cycle, but for a whole generation!

This very long decline in interest rates has caused investment asset prices to get a ‘free kick’. An investment in bonds during this period benefitted from the capital appreciation caused by the progressively lower rates. Shares and real estate have benefitted from the concept of yield compression – lower interest rates allowing share earnings yields to be lower, (hence higher share prices and P/E ratios), and real estate valuations have benefitted from much lower capitalisation rates. Consequently, all of these investment categories have delivered higher average returns over the last generation than they would have if interest rates were steady, or rising.

Unfortunately, the party is over. Interest rates are now at or near their historic low point, and are unable to fall much further. Consequently, asset prices will no longer benefit from the ‘free kick’ provided by falling rates. Take the Australian stock market as an example. Between 1961 and 1989 the average price/earnings ratio of the market was about 10 times. This means that the valuation (price) of shares was about 10 times their average annual profit. This high 10% yield was necessary because interest rates (an alternative investment choice) were also very high. Since 1990 (the period of declining interest rates) the price/earnings ratio has been about 16 times, a profit yield of 6.25%. In other words, shares (the same or similar companies - BHP, Westpac, Boral, AGL etc.) have been priced 60% higher relative to their profit in recent times, compared to how they were priced during the high interest rate era, not because company profits or GDP are better these days, but just because rates have fallen. Now, the good news is that interest rates are not going up any time soon, so stock prices will maintain their high valuations and price/earnings ratio. Share investors will still benefit from occasional periods of strong profit and economic growth, but need to be watchful, as any material rise in interest rates could erode stock market valuations.

Australian Shares

The Australian stock market continued its positive trend in the first quarter of 2017, rising by 3.51%, or 4.82% including dividends. The Total Return index, which is the best gauge of market performance as it includes dividends, reached successive all-time highs during the quarter.

There were a series of positive events and indicators that caused the market to rise. Australia’s GDP improved in the December quarter, after a previous quarter decline; company profits were reasonable; interest rates remained at historic lows; and the US stock market continued to rise. The bank share index, being primarily the four leaders, plus Macquarie and the regionals, outperformed the broader market in the quarter. This small group of companies accounts for an astounding 30% of the Australian stock market, so if they go up, the market rises, and vice versa. Investors need to be aware of the concentration risk caused by the banks representing such a large proportion of our market – should operating conditions for banks deteriorate, the overall market would likely fall sharply.

Commodities enjoyed support from more accommodative Chinese policies and their buoyant real estate market in mid to late 2016, but prices have retracted recently. Mineral based stocks such as BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto have exhibited significant and unpredictable earnings volatility in recent years, so we are inclined to remain only modestly invested in this sector. Oil and gas export prices have been largely steady, but domestic wholesale energy prices have become very erratic.

Australian share prices are currently a bit high. Our fundamental analysis requires the projected share returns to be at least twice the prevailing risk free rate. For example, risk free investments (government bonds/term deposits) are currently about 2.7%, so projected share returns need to be at least 5.4% to adequately compensate investors for the risk taken. At present, we are projecting a lower return, so we are inclined to hold fewer shares and more cash than normal, which can be achieved by selling some higher priced stocks into the current market rally.

We have maintained a higher than usual cash position in our managed share portfolios, due to some share sales last quarter. We recently also sold shares in Goodman Group, the strongly performing industrial property company, thereby exiting the last of the property related investments in our domestic share portfolio. In our managed portfolio CSL, Spotless, Wesfarmers, Westpac and Woolworths all performed well in the March quarter, whilst BHP Billiton, Brambles, Santos and Telstra made negative contributions.

Looking forward, there are risks and uncertainties that cause us to maintain a cautious approach. Our primary concern is that share prices are rising, despite a general lack of sustainable economic growth, coupled with very high consumer debt, a stretched residential real estate market, and worrying trends in the labour market.

Global Shares

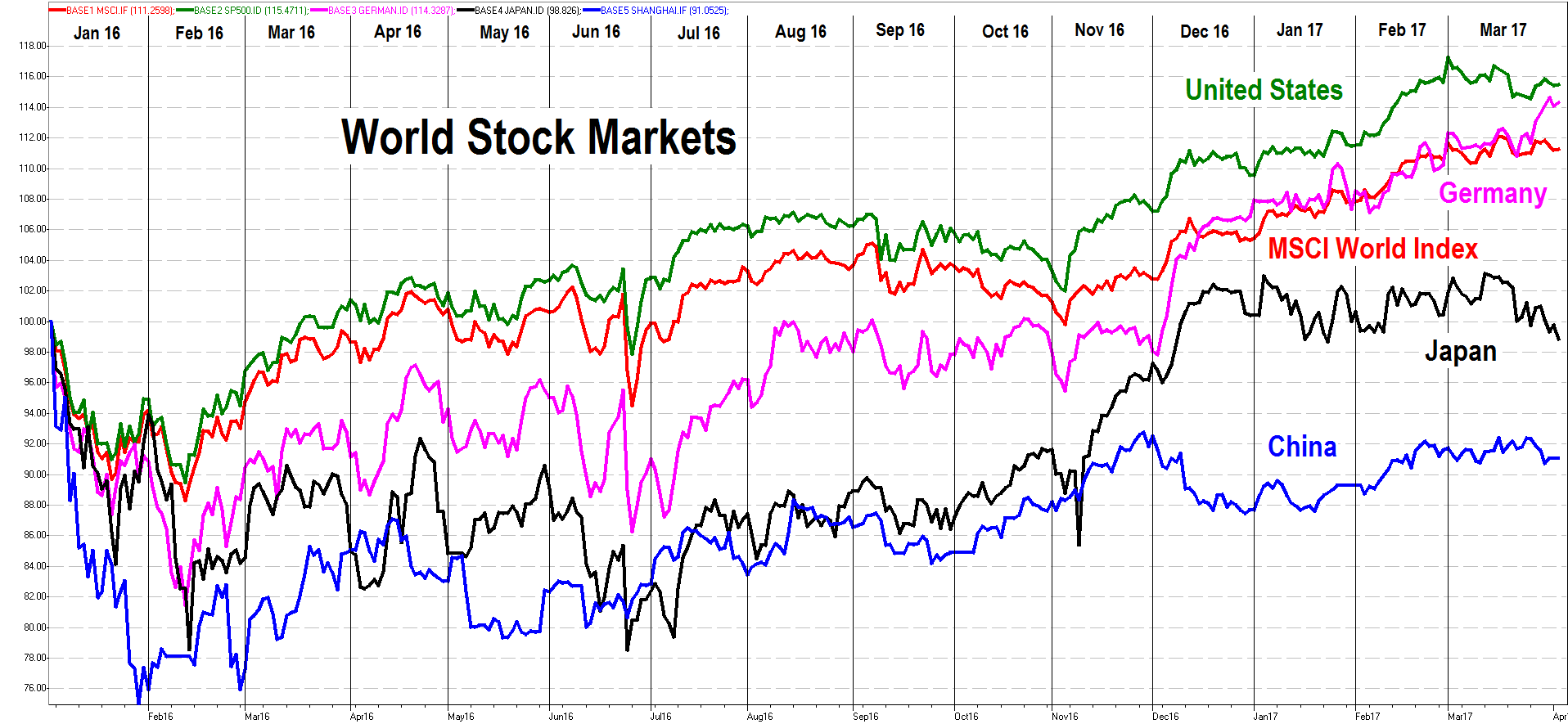

Most international stock markets enjoyed solid gains in the March quarter, buoyed by the ongoing post-election rally in America. Optimism was fueled by the expectation that some economic inflation was returning, particularly in China where the produce price data finally turned positive and in the United States on the back of improved consumer and business confidence.

In Europe, the election in Holland and the Italian referendum showed further support for alternative populist policies, and this will likely also be the case in the forthcoming French presidential election. Nevertheless, markets were largely unconcerned, preferring to focus on lower volatility and more positive economic signals, at least for the time being. Britain is progressing with its painful Brexit process, and this had the effect of further weakening the Pound.

Within our managed portfolios, we favour some of the European healthcare stocks such as Roche (Swiss listed pharmaceuticals) and Novo-Nordisk (Danish listed diabetes care), and some of the predominately US listed technology focused companies such as Alphabet (Google), MasterCard and Priceline (booking.com). Generally speaking, the fairly high price of shares has temporarily limited the value proposition of most global stocks, so we are maintaining a higher than usual cash component, which we expect to redeploy to some of the better quality stocks when appropriate opportunities emerge.

Property Securities

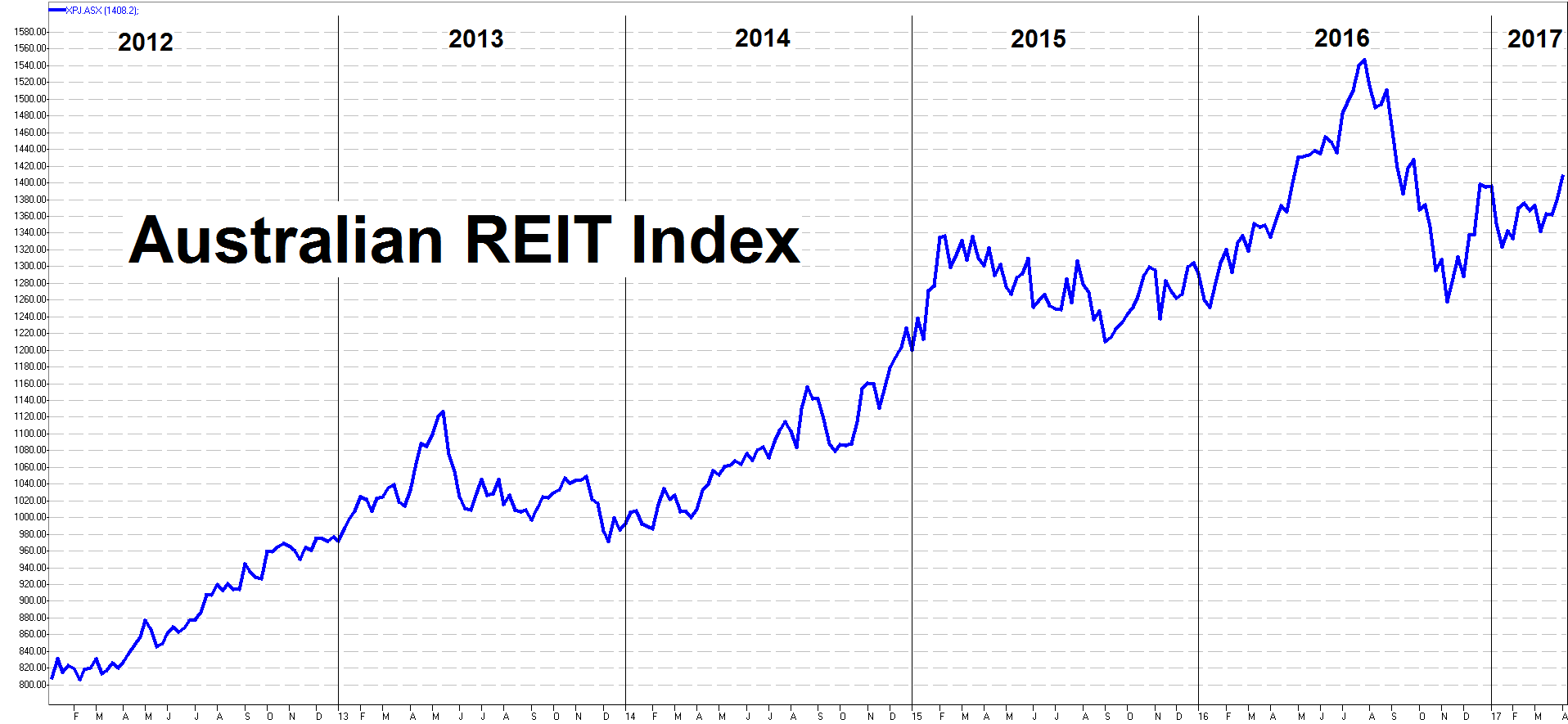

The market value of the listed Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) index fell marginally in the March quarter, thereby underperforming the broader stock market. The retail sector property REIT’s, Westfield, Scentre, BWP (Bunnings), and Vicinity had a weak quarter, whilst industrial and investment management REIT’s including Goodman and Charter Hall performed well.

Scentre Group, the owner of the Westfield branded shopping centres in Australia and New Zealand, recently announced that the value of their flagship asset in Sydney’s Pitt Street Mall had reached an eye-watering $4.5 billion, helped by a capitalisation yield of just 4.25% for the Sydney City retail component. This got me thinking…... firstly, what a marvelous piece of real estate it is that commands such a valuation, and secondly how wafer thin the yield is relative to normalised risk-free interest rates. Clearly, commercial property is enjoying the same valuation phenomenon as residential real estate. Interestingly, the share price of Scentre has declined 15% from its 2016 peak, notwithstanding their strong property valuation growth – the stock market can be a canny prophet, and seems to be suggesting that real estate prices have peaked.

We have maintained a lot of cash in our managed REIT portfolio. We will likely retain this high cash component whilst security prices trade at an unreasonable premium to the underlying property net tangible value, and whilst a large proportion of reportable profits are coming from property revaluations, rather than rental income.

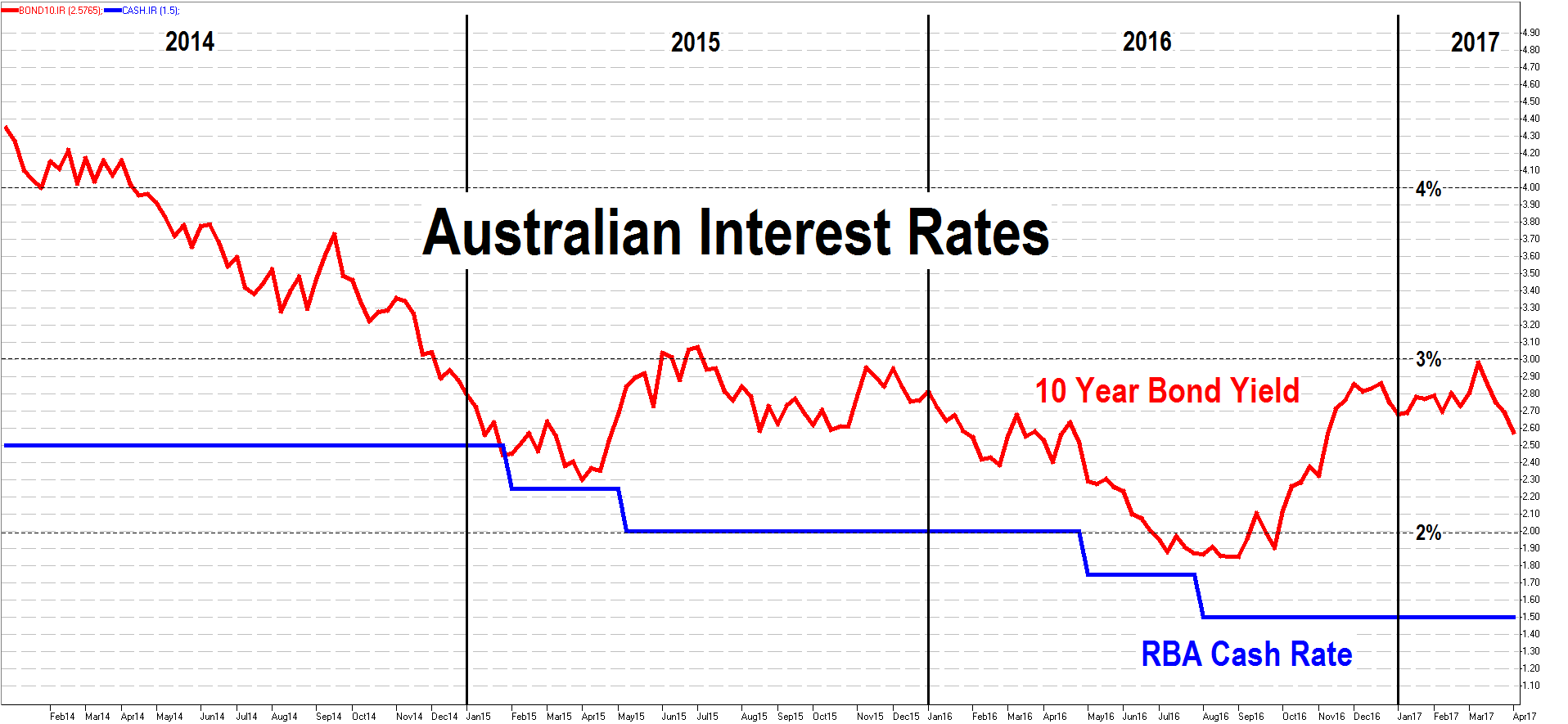

Interest Rates

The Reserve Bank of Australia is in a quandary. They would dearly like to use their monetary tools and raise interest rates to curtail asset price speculation, but can’t do so for fear of pricking the real estate bubble, and damaging our terms of trade by causing the currency to rise. Instead, the RBA has joined their regulatory colleagues APRA (bank regulator), ASIC (financial services & corporate regulator) and the finance minister to ‘media jawbone’ the very real problem of the massive buildup of consumer debt, and the considerable economic risks posed.

Consequently, it is likely that short term interest rates, including cash and term deposit rates, stay very low for an extended period. This is not good news for investors seeking a higher return, but these investments will provide strong capital preservation, which should not be overlooked.

The listed income security and hybrid market has been fairly steady, and continues to provide a decent income return, albeit with higher risk. The credit spreads and trading margins that affect pricing of this sector have been narrowing, which reflects improved investor appetite and slightly higher prices. However, these securities (mostly issued by banks) can become volatile, typically due to either concerns about finance sector robustness, or a surplus of new issuance. Consequently, we are generally reducing exposure to longer duration hybrids, to mitigate some capital risk.

In America, the Federal Reserve raised their Federal Funds interest rate in December to 0.75%, in March to 1%, and indicated several more rises over the course of 2017. They also indicated a preparedness to reduce their balance sheet size, by beginning to unwind the quantitative easing (money printing to buy bonds) program. The timing of this is uncertain, but the market effect could be considerable as the Fed is holding assets of US$4.5trillion. Clearly, the very long downwards trend in interest rates is over, so bond and other asset market risks will have increased.

Outlook

Some share prices and markets are high, and some districts and sectors of real estate are also high. Further immediate upside potential is difficult to envisage, despite these valuations continuing to be supported by low interest rates.

Consequently, share and property investors should err towards more of a capital preservation strategy, and be prepared to hold a higher proportion than usual in cash and term deposits, notwithstanding the low applicable interest rates.

The Australian economy has some worrying signs. Consumer debt is a huge problem, and the ability to arrest this is constrained by increasing under-employment and very low wage growth. It’s likely that economic indicators such as consumption and GDP will weaken, but with luck, strength in the tourism and construction activity sectors will mitigate the downside. Here’s hoping that there isn’t a sharp shock, such as a slowdown in Chinese commodity demand or a house price slump.

Disclaimer & General Advice Warning

This publication has been prepared by Joseph Palmer & Sons (ABN 29 548 490 818) an Australian Financial Services Licensee (AFSL 247067). Whilst the information contained in this publication has been prepared with all reasonable care from sources, which Joseph Palmer & Sons believes are reliable, no responsibility or liability is accepted by Joseph Palmer & Sons for any errors or omissions or misstatements however caused. Any opinions, forecasts or recommendations reflects the judgment and assumptions of Joseph Palmer & Sons as at the date of publication and may change without notice. Joseph Palmer & Sons, their officers, agents and employees exclude all liability whatsoever, in negligence or otherwise, for any loss or damage relating to this document to the full extent permitted by law. This publication is not and should not be construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment. Any securities recommendation contained in this publication is unsolicited general information only. Joseph Palmer & Sons are not aware that any recipient intends to rely on this publication and are not aware of the manner in which a recipient intends to use it. In preparing our information, it is not possible to take into consideration the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any individual recipient. Investors must obtain individual financial advice from their investment advisor to determine whether recommendations contained in this publication are appropriate to their personal investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs before acting on any such recommendations.